Market experts — and even some of those involved in the energy trade — say it’s not so clear.

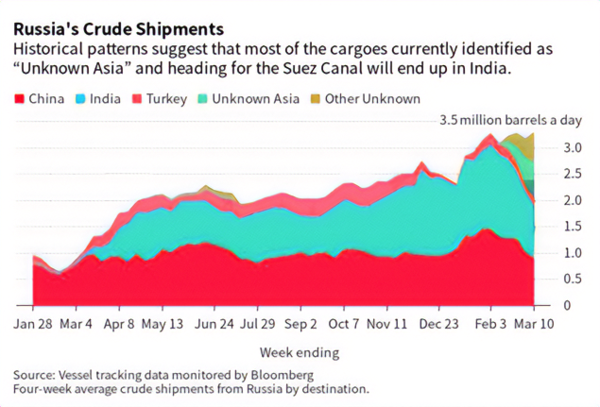

India’s consumption of Russian crude was minimal and sporadic before President Vladimir Putin’s forces attacked Ukraine, but it has soared since, becoming a key tool for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s bid to fight energy inflation.

Yet the structure of India’s oil trade means that the final price it pays includes shipping, insurance and other costs upon arrival at its ports, without a detailed breakdown. That makes it hard to know how much it’s actually paying Russia, and whether it’s undercutting the goal of limiting Moscow’s revenue from crude sales.

“The reality is this market has become extremely opaque,” said Vandana Hari, founder of Vanda Insights in Singapore. “It is near-impossible to get middlemen costs.”

Uncertainty about how much India pays is part of the murkiness around Russian oil flows more generally, as the trade shifts from the Atlantic basin to Asia and from large traders to smaller entities. And it highlights the uphill struggle by Ukraine’s allies to enforce or even encourage compliance with the curbs imposed over the past year.

India’s oil ministry, Ministry of Commerce and Ministry of External Affairs did not respond to requests for comments.

Since Modi’s government never signed up to the G-7 cap, it doesn’t have an obligation to comply with it — so long as it is not using Western insurance or shipping services. And while people familiar with the matter say the government won’t break the sanctions — and has asked banks and traders to adhere to the rules — the challenge comes in monitoring or enforcing such vows.

For instance, to supply buyers in places such as India and China, which continue to rely on Russian crude, a “gray fleet” of tankers has emerged.

That’s helped push down the costs of crude transport overall, according to Viktor Katona, lead analyst at Kpler. But the rise of the gray fleet and other middlemen in the Russian oil trade makes dissecting price data even harder, and official figures are of little help.

Data from India’s Ministry of Commerce show that the nation’s average price for Russian crude in January was $79.80 a barrel, significantly higher than the $60 cap. That final price, which includes shipping, insurance and other expenses, would imply extraordinary logistics costs if the cap wasn’t breached during that month.

The difference between the landed price — the cost when oil arrives at port — and the free-on-board price, which doesn’t include shipping, insurance and other ancillary fees, is the crux of the problem. Moreover, India often secures its oil after it’s in transit, having already left Russia and adding to the complexity of determining the original price.

According to the two companies that have long published Russian oil prices — Argus Media Ltd., whose data have for years determined the export duties that Moscow gets from overseas sales, and S&P Global Insights, which is better known by traders as Platts — the price paid at the point of export is far below the price cap.

Argus data for the end of February showed the export price of Urals, Russia’s flagship grade and the variety that India is really snapping up, at about $45 per barrel. Platts, which assessed it at similar levels, also publishes a delivered-to-India price for the Urals grade. That price — which includes delivery costs — has been above $60 a barrel since Jan. 18, when Platts started it, and stood at $64.31 on March 10.

If correct, those analyses are good news for the Biden administration, which is eager to have large emerging nations support its efforts to stymie the Russian war machine while ensuring uninterrupted flows.

A US government official, who asked not to be identified discussing non-public information, said point-of-export (FOB) prices published by Argus Media and Platts are seen as the best indicators of Russian revenues, and the data are consistent with what the Treasury heard anecdotally, even if he acknowledged the opacity of the situation.

But then there are recent purchases by Indian refiners of Russian ESPO crude loading from the Far East and trading at a price above the flagship Urals blend, according to Asian traders, suggesting higher values are not out of the question.

Another group of researchers who got access to invoice data for Russia’s oil exports estimated that Indian firms paid an average of $64 per barrel for Russian oil in the weeks after the price cap began.

Refinery officials in India, who asked not to be identified discussing sensitive issues offered no explanation for how precise compliance with a $60 cap would be established. From the delivered price, one official pointed out, it is simply not possible to be sure of the purchase price.

While the US and its allies say they believe India is buying below the cap, they would be loathe to single out Delhi for criticism regardless. No government wants to alienate the world’s most populous nation which, beyond the dynamics of the war in Ukraine, is seen as a critical swing-state in rising US-China tensions.

On Tuesday, a US official said the bulk of Russian seaborne oil — about 75% — is being traded without the use of western services. And the official, Assistant Treasury Secretary Ben Harris, said that while there is some “subversion” of the price cap likely taking place, he said Russian Finance Ministry data show that revenue to Moscow is down.

For now, though, the uncertainty threatens to slow purchases, as Indian refinery executives and banks struggle with the additional information required because of sanctions and the price cap. That’s because even if India isn’t a party to the price cap, its banks and other companies want to avoid potentially breaking sanctions.

The looming question in the months ahead is whether the Western approach will last. Will Washington and its allies seek to tighten penalties on Russia as the war enters its second year, or opt for a more laissez-faire approach in favor of ensuring continued flows?

“They are trying to tailor the carrots and the sticks,” sanctions expert Maria Shagina of the International Institute for Strategic Studies said, explaining US assertions on compliance, and the avoidance of accusations. “It is impossible to have it watertight. It’s about the scale of the leakage.”